Here’s a sentence which might sound a little odd: higher interest rates have been good news for the UK economy.

For the first time in many decades, the pain faced by borrowers from higher interest rates has been more than balanced out by the benefit experienced by savers from those interest rates.

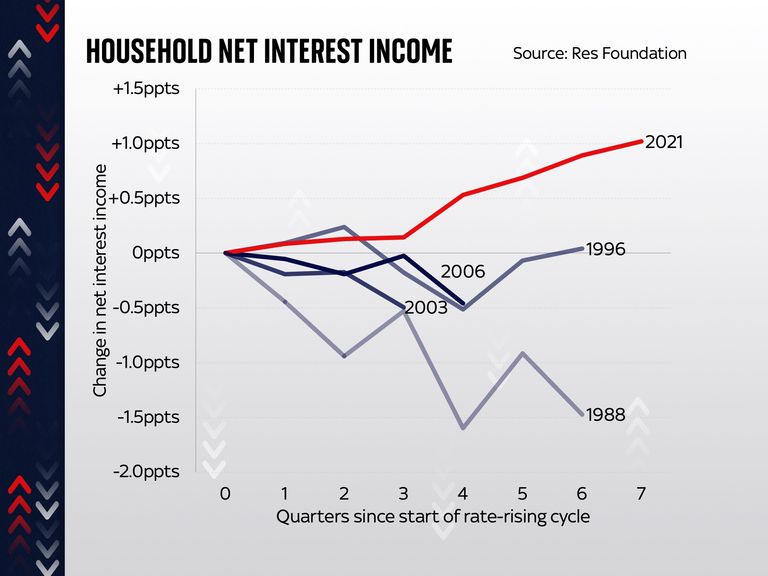

If this sounds a little odd it’s partly because invariably, when people – the media, politicians and economists – talk about interest rates they focus unduly on one side of the equation: the plight of the borrower. And there’s an understandable reason for that: in previous “hiking cycles”, when the Bank of England raises interest rates, that pain has invariably outweighed the windfall.

Money latest: Mortgage price war ‘likely’ as 3% interest rates predicted

That was the case when borrowing rates were lifted in 1988; it was the case in 1996, in 2003 and in 2006.

In each case the overall impact, across the economy, on households’ balance sheets was negative.

But not so this time around.

According to the Resolution Foundation, the net income we’ve earned, across the economy, as a result of interest rates, has actually risen rather than fallen – up by a percentage point since rates started going up.

To put that into perspective, the “interest rate effect” on incomes in the late 1980s was -1.5 percentage points.

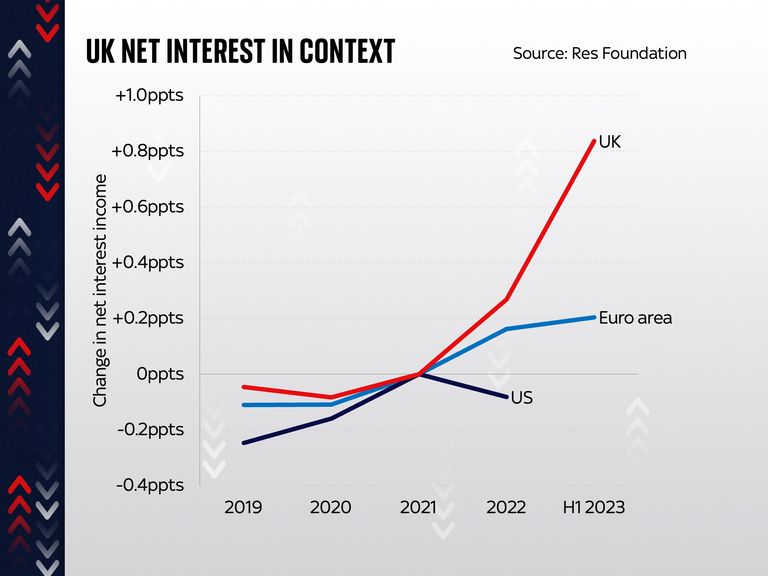

And what’s striking, when you compare the UK to the euro area and the US, is that we are a bit of an outlier: the interest rate effect, across the economy, was much more positive than it was in those two other areas.

This, says the Resolution Foundation, is at least part of the explanation for how the UK hasn’t yet slipped into the recession a lot of people anticipated this time last year.

Part of the explanation for this is that it so happened, in large part because of the pandemic lockdowns, that people began this hiking cycle with a lot of savings in their bank accounts – far more than usual.

Read more:

Mortgage approvals up as more lenders cut rates

First-time buyers fall to ‘lowest level in a decade’

FTSE 100 bosses ‘earn typical UK annual salary in three days’

The upshot was that, across the economy, the benefit from those savings (and savings rates went up very quickly – albeit not to the levels of borrowing rates) was greater than the impact on mortgages and loans. Another part of the explanation is that so far only around half of those with fixed-rate mortgages have re-fixed their loans.

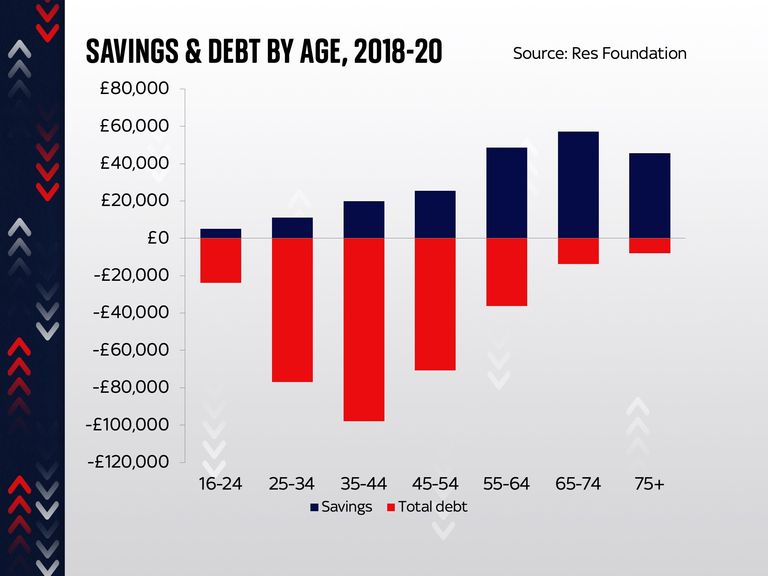

But there are a few very important provisos here. The first and perhaps most important is that while the above is certainly true across the whole economy, there’s a dramatic difference of experience for different categories of people.

Those whose debts outweigh their savings (which in this case mostly means younger people) will certainly see a negative impact from higher rates. Those with far more savings than debts – the older segments of the population – will see a benefit. In other words, the pain and the dividends are not being equally shared out. The old are doing much better; the young are doing worse.

And there are two other provisos. The first is that this positive impact will begin to wear off as more and more people re-fix their mortgages and go up from low-interest rates to higher rates. Even though the typical fixed-rate deal has been coming down recently, it’s still far higher than it was two or five years ago.

Click to subscribe to The Ian King Business Podcast wherever you get your podcasts

The final proviso is that none of the above takes into account the broader impact of the cost of living crisis.

Everyone is having to pay higher prices for nearly everything. And while the annual rate at which those prices are increasing (inflation) has decelerated, the level of prices remains more than 15% above where it was a couple of years ago.

That’s a painful adjustment for everyone. The good news is that the impact of rates – across the economy as a whole – has actually been positive rather than negative. But not everyone will be seeing the benefits.